In 2013, US Vice President Joe Biden visited Colombia and met with then-President Juan Manuel Santos to cement ties between the two countries. Just a year before, a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) had been ratified between the two which proponents held would be beneficial for both. “The free-trade agreement is just the beginning,” Biden declared. “We’ve doubled visa validity from five to 10 years. As was pointed out, we championed the Colombian accession to the OECD. We are prepared to talk with Colombia about the TPP (Trans-Pacific Partnership). We are anxious to continue to engage with and integrate the economies of the region. And it makes sense for everyone,” he added at the press conference in Bogota on May 27, 2013.

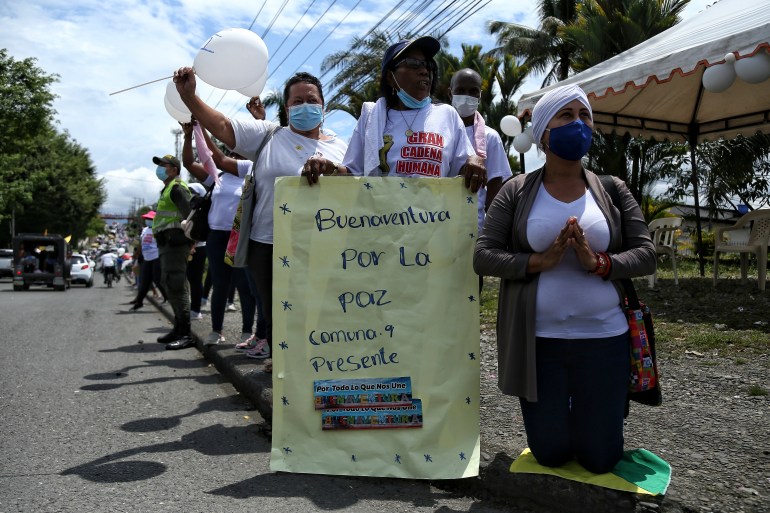

But, eight years on, social leaders, economists, and leaders of Afro-Colombian semi-autonomous community councils question if the US-Colombian FTA really made sense for everyone. Despite the National Infrastructure Agency’s large port concessions to handle the increased trade – and Afro-Colombians frequently providing the low-cost labour for such port expansions – those living in and around the port city of Buenaventura have not shared in the wealth that increased trade has produced. Furthermore, they continue to suffer violence from new paramilitary groups which aim to capture legal and illegal rents. As part of this year’s deadly, weeks-long National Strike in protest against austerity measures that would have reduced fiscal deficits by taxing the poor and middle class, residents of Buenaventura prevented cargo from entering the country, demanding better living conditions for its 415,000 inhabitants – many of whom have no running water – and more funding for the violence-ridden city. Nationwide, at least 80 people were killed in the protests, many of whom were Black. One police officer died. But those living in Buenaventura are used to this sort of state and para-state violence and feel they have little to lose by taking part in such protests.

During the Cold War, the US propagated “counterinsurgency” policies in Colombia, especially after the Cuban Revolution. In 1962 – two years before the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) was founded – American General William Yarborough instructed the Colombian military to make “mixed units of civilians and militaries” to prevent the spread of communism. In the 1990s and 2000s, paramilitary, or self-defence, forces increased dramatically, culminating in the United Self-Defence Forces of Colombia (AUC), to fight left-wing guerrilla groups such as the FARC. In the mid-2000s, “Bloque Calima” of the AUC terrorised people living in Buenaventura to kick out left-wing guerrillas and ensure a social control friendly to international investment. Despite the official 2005 demobilisation of AUC paramilitaries through an agreement with the government – the Peace and Justice Law 975 – the violence has continued. In 2014, civil society groups denounced the presence of chophouses, where paramilitary groups dismember people alive as a strategy to use fear for social control. In February of this year, there were 30 days of firefights in the port city of Buenaventura with the government claiming that these were “turf war” disputes between rival gangs. Advocates for victims and those who work with community leaders, however, see a continuity between what has happened this year and previous cycles of violence between illegal armed groups hoping to seize control of territory. “The turf war narrative is problematic because it diminishes the responsibility [of the state] and it makes it micro instead of macro. New problem – fixed the old one – so it’s not connected. But in reality, it’s all connected. Foot soldiers may change, but the whole dynamic is the same. Many different names of the groups but it’s the same issues,” says Gimena Sanchez from the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), a Washington-based NGO which advocates for human rights in Latin America. Colombian human rights advocate Enrique Chimonja, who has been helping to organise peasant, Indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities for decades, including communities in Buenaventura, agrees. “In my judgement, it’s very simple, it’s to distract attention from what really is happening in Buenaventura. It is really a territorial displacement strategy to dismantle the principles of Law 70 [which safeguards the rights of Afro-Colombian communities], to evict people from collective lands,” he said. Chimonja sees the continuing paramilitary group activity as a strategy by private companies to evict people living on their collective lands in order to accommodate port expansion required not only by the free-trade agreement with the US but also by the 16 other FTAs Colombia has signed.

Colombia has one of the largest populations of African descent in the Americas. The Afro-Colombian population has been in Colombia since the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors in the 16th century and today continues to be heavily concentrated on the country’s Pacific coast. Slavery was abolished in 1852 and most of the formerly enslaved people stayed in the communities they had lived in since being brought to Colombia, which gave way to the culture and traditions of those areas that continue to this day. Despite their semi-isolation from the rest of Colombia, the communities on the Pacific coast were still subject to the same laws created by the centralised state in far-away Bogotá where Afro-Colombian communities were seldom even an afterthought following emancipation and when legislation was written. This changed with the 1991 Constitution, a result of tremendous social upheaval and a peace agreement between the Colombian government and various left-wing rebel groups. The government had signed an agreement with the M-19 guerrilla organisation in late 1989, which required constitutional reforms to be implemented. In early 1990, these reforms failed to pass in the congress, leading to a political crisis, and the student movement “seventh ballot” emerged, which called not only for constitutional reform but a whole new constitution. Aside from the M-19, which was already in the process of demobilisation, the Popular Liberation Army (EPL), the Revolutionary Workers Party (PRT) and the Quintín Lame Armed Movement (MAQL) also went through demobilisation processes so they could participate in the Constitutional Assembly.  The 1991 constitution placed a special emphasis on the rights of ethnic minorities in Colombia and in 1993 was codified for Afro-Colombian communities in Law 70. Law 70 (PDF) granted Black communities on Colombia’s Pacific coast the right to collective ownership of lands they have already occupied for more than 300 years. It formalised their right to maintain their unique lifestyle and culture while aiming to promote economic and social development. Article 5 of the law facilitated the creation of “community councils” in Afro-Colombian communities, responsible for the internal administration of collective land titles. Community councils delimit and assign the boundaries of the collective lands, and are responsible for the conservation and protection of the collective territory, protection of cultural identity and the election of their legal representative.

The 1991 constitution placed a special emphasis on the rights of ethnic minorities in Colombia and in 1993 was codified for Afro-Colombian communities in Law 70. Law 70 (PDF) granted Black communities on Colombia’s Pacific coast the right to collective ownership of lands they have already occupied for more than 300 years. It formalised their right to maintain their unique lifestyle and culture while aiming to promote economic and social development. Article 5 of the law facilitated the creation of “community councils” in Afro-Colombian communities, responsible for the internal administration of collective land titles. Community councils delimit and assign the boundaries of the collective lands, and are responsible for the conservation and protection of the collective territory, protection of cultural identity and the election of their legal representative.  The law aims to guarantee that Afro-Colombian communities receive real opportunities that are equal to the rest of Colombian society. It also gives them the right to consultation if the government or private industry want to use their land for economic development projects. This right is meant to guarantee the autonomy of a community council’s control over how collective land is used. In theory, this gives historically marginalised communities control over their lands, which they often use for small-scale agriculture. Unfortunately, this does not always happen in practice. Francia Marquez, who won the Goldman Environmental Prize in 2018 for defending her land from mining and who recently announced her candidacy for the presidency, wrote her undergraduate thesis on violations of previous consultations in Afro-Colombian communities in the Cauca department, which borders Buenaventura.

The law aims to guarantee that Afro-Colombian communities receive real opportunities that are equal to the rest of Colombian society. It also gives them the right to consultation if the government or private industry want to use their land for economic development projects. This right is meant to guarantee the autonomy of a community council’s control over how collective land is used. In theory, this gives historically marginalised communities control over their lands, which they often use for small-scale agriculture. Unfortunately, this does not always happen in practice. Francia Marquez, who won the Goldman Environmental Prize in 2018 for defending her land from mining and who recently announced her candidacy for the presidency, wrote her undergraduate thesis on violations of previous consultations in Afro-Colombian communities in the Cauca department, which borders Buenaventura.

In the Afro-Colombian community on the Naya River, which forms the border between the departments of Cauca and Valle del Cauca, armed actors brutally benefitted from the area’s isolation at the height of the armed conflict in the 1990s and 2000s, according to Rodrigo Castillo, a member of the Naya River Community Council. The FARC first arrived in the 1980s, followed by the Cuban inspired National Liberation Army (ELN) in the 1990s, which used the river to grow coca plants and as a route for drug trafficking. The right-wing AUC moved in in April 2001 and killed more than 100 people they claimed were sympathisers of the guerrilla organisations. More than 3,000 people were displaced to urban areas in Buenaventura and neighbouring Cauca. The arrival of the conflict to the region pushed out large numbers of people while simultaneously bringing coca cultivation and illegal mining to the territory, a prime source of funding for illegal groups in Colombia from right-wing paramilitaries to FARC dissidents who refused to disarm. The displaced now find themselves in cities that are very different from the rural areas in Colombia’s Pacific coast river communities, which forced them to adapt to a new, harsh and often violent reality of poverty, economic exploitation, and crime in Buenaventura, Cali, and other large cities. For María Miyela Riascos, a community leader in Buenaventura, the difference in life between the river communities and the urban area is stark: “Before 2000, we lived in our territories in extreme neglect from the Colombian state with the state failing to provide adequate healthcare, education, and a way to make money. Nobody gave us anything but we had our own seeds and knowledge. We worked together as a community. Everyone had something to eat from what we produced. Our river was clean and there were abundant natural resources.”

Law 70 and the community councils in the rural areas near Buenaventura stand in tension with the policy of economic opening-up, which has been state policy since the late 1980s. This is marked by low tariffs, a reduction in state subsidies and privatisation. Afro-Colombian community councils are based mostly on small-scale agriculture and artisanal fishing, in which the preservation of the environment is an integral part. The “economic opening” is a model of development based on the exploitation of natural resources for the generation of profit; under this model, using the land more efficiently is prioritised. Buenaventura was an early example of these new economic policies when Colombian President Cesar Gaviria privatised the state-run port, Colpuertos, in 1994, and the new Sociedad Portuaria de Buenaventura changed its technical capacities to make port activities more capital-intensive rather than labour-intensive. The new, private owners introduced “labour flexibility” measures. These changes reduced the labour force from 10,000 in 1990 to 4,200 in 1996, and the average salary of a port worker fell by 70 percent. Furthermore, the private port often brought workers from outside Buenaventura for higher-wage jobs, creating a separation between the private port and the community living in Buenaventura. Colpuertos, on the other hand, had provided working-class bonaverenses with stable jobs and good benefits, enabling them to support their families. Eight port labour unions formed during the operation of Colpuertos, creating a bond between the communities living around the port and the port itself. Privatisation hollowed that out. Deepening the economic opening, Colombia signed its Free Trade Agreement with the US in 2006, but the US Congress held up ratification until 2012 because of Colombia’s poor record on labour rights. Proponents held that the free-trade agreement would increase Colombian exports and access to international markets, resulting in economic growth for the country as a whole. Despite these promises, since 2012, Colombia has gone from a trade surplus to a trade deficit, and its dependence on primary material exports – oil, coal, coffee, bananas – has increased. The FTA lowered tariffs on imported goods, making them cheaper than those produced domestically. In fact, productive sectors of the economy such as the industrial sector, have decreased as a percentage of GDP. Food sovereignty is another issue. In 2012, US corn represented 5 percent of the market share in Colombia, but by 2018 it represented more than 97 percent of the market share. The US’s superior infrastructure, technology, machinery, genetically modified seeds, and state subsidies give US corn a competitive advantage. “The FTAs have been disastrous for Colombia. They have flooded Colombia with products and the Colombia that we dreamed of and built, that my parents and grandparents had built… all this disappeared with the FTA,” Riascos says.

As a result of the FTAs, Buenaventura has seen a 42-percent growth in international trade during the decade of 2010 to 2020. It has also undergone a number of port expansions including a $200m mega-project, the Buenaventura Containers Terminal (TC Buen), which has also displaced people from surrounding neighbourhoods to make way for construction. Four hundred families from the Santa Fe neighbourhood were affected by the construction of the TC Buen but were refusing to leave. A mysterious fire started in 2013, burning down 25 homes precisely where TC Buen was being constructed and displacing 196 families. Other families claimed there was pressure from paramilitary groups to leave. Port leaders, however, denied any sort of wrongdoing. Many of those displaced by the project had also been previously displaced from the semi-autonomous Black communities on Colombia’s Pacific coast. Snyder Rivera, an economist with the Colombian organisation Cedetrabajo, which monitors the implementation of free-trade agreements, says advanced port logistics have been prioritised over the needs of the people living collectively in and around Buenaventura. “The port has improved and is considered competitive but in the areas around Buenaventura, there is a lot of poverty, scandalous levels of wealth inequality, a high level of criminality. This has to do with the historical debts of the Colombian state not only to Buenaventura but to the whole Colombian Pacific,” Rivera says. He is referring to the lack of investment and attention the central government has given the port of Buenaventura, reflected in the high levels of poverty, lack of access to water and healthcare, the ongoing presence of illegal armed groups, and high unemployment. In 2017, therefore, people in Buenaventura organised a general strike demanding better conditions. Overall in Buenaventura, nearly 17 percent of the population still have unmet basic needs. By comparison, in Bogotá, the capital, only 3 percent of the population live in those conditions. Riascos also believes that international trade has been prioritised over people. “I’ve been to the port of Vancouver and its technology and functioning is comparable with Buenaventura, Buenaventura has nothing to be jealous of. The difference is how the people live in Vancouver and how people live in Buenaventura, there, there is a difference,” she says. In Buenaventura, the sort of development by those who envision and implement the free-trade agreements and the needs of rural, agrarian community councils and Indigenous communities stewarding the land are in conflict. Ultimately, Riascos says, the government and powerful international economic interests have only benefitted from the displacement of Afro-Colombian people from their traditional lands. “What they [the government and paramilitary groups] do in the name of neoliberal economic development is criminal. And they go through whoever they have to, whatever they have to, to achieve their perverse goals that hurt Buenaventura, consolidating structural racism and displacement.”